文章

Special Report: Industrial Property – Restoring Sustainable Industrial Manufacturing by Mr. David Nardone, Presiden and CEO of Hemaraj Land And Development Plc.

30/04/2010Industrial Demand Is Returning to Thailand and Global Markets

In early 2010, manufacturing demand and thus production levels are improving in Thailand. From the low points of mid 2009, durable goods consumption, production, and overall exports have all begun to pick up. This upward trend also reflects the pattern of emerging markets experiencing a faster recovery than mature developed markets. Thailand’s GDP is now projected to grow by 3.5% to 4.5% for 2010, a substantial improvement from the earlier forecasts of only 2%. Manufacturing, which comprises 35% of Thailand’s 2008 GDP of approximately 9 trillion baht, is significantly important, as are exports, which totaled 5.2 trillion baht in 2008.

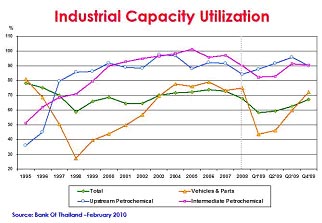

Looking at leading indicators, manufacturing capacity utilization, upstream and intermediate petrochemical capacity utilization declined from the mid 90’s percentile in late 2008 to the low 80’s percentile in 2009. Automotive vehicle and parts capacity utilization declined from 75% in 2008 to the mid-40s percentile in middle of 2009, reflecting the severe local and global contraction that affected Thailand’s export base. Yet, the end of 2009 and the beginning of 2010 have seen a remarkable bounce back to near pre-crisis manufacturing capacity utilization levels.

The Board of Investment 2009 final investment approvals were reasonable with 1,003 projects approved and baht 281 billion baht of investment. There were a large number of applications submitted, given the expiry of special investment year incentives, which should be extended through 2010, though, given poor 2009 investment conditions.

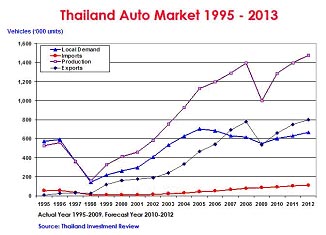

Vehicle demand in 2009 was almost evenly divided between domestic sales (548,000 units) and exports (536,000 units). Total 2009 production was 999,000 units, a decrease of 28% from 1.39 million units manufactured in 2008. However, 2010 has started strong with sales of 50,000 units and production of over 100,000 vehicles in January of 2010. Projections for 2010 are for domestic sales of 580,000-600,000 units and total production of 1.35 to 1.4 million vehicles.

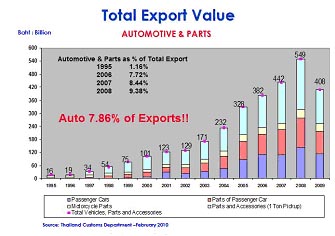

Automotive exports have steadily increased since the mid-nineties, reaching almost ten percent of Thailand’s total exports in 2008 before declining in 2009. Equally significant is the broadening of exports from only one-ton pickups to include passenger cars as well as automotive parts, reflecting the export supplier base for tier one suppliers. Thai vehicles and parts are exported to more than 100 countries and prospects have increased with ASEAN and other Free Trade Agreements.

Map Ta Phut Negative For Investment

With the current pace of legislation and procedures for Health Impact Assessments, it is hard to contemplate how any companies will receive their Environmental Health Impact Assessments (EHIA) approvals in 2010. This could mean up to a 12 to 18 month delay for dozens of projects, costing billions of dollars and affecting employment, directly and indirectly, of tens of thousands of Thai workers. It is critical, therefore, to expand and model the just announced court approved mechanism in order to enable all projects to continue with construction in parallel with the EHIA at a minimum, so that additional extensive operational, financial, and supply chain losses will not be further incurred. In addition, most developed countries that have HIA assessments undertake the assessment during the operation, not prior to construction at all. This method would be fair for all the existing projects due to operate or that were operating prior to the HIA requirement and they could then undertake the EHIA in parallel if their EIA and permit are approved.

It is necessary for the government to accept responsibility and to mitigate losses that resulted from the failure of successive governments to promulgate the necessary laws and procedures to enable investors to comply with the Constitution. This is the key to rebuilding the loss of confidence on the part of both Thai and foreign investors. The actual situation of companies having complied with all known requirements and having obtained environmental approvals, industrial estate permits, Board of Investment promotion certificates, etc, and subsequently in good faith entered into contractual operational and financial commitments based on those approvals was quite reasonable based on the existing legal and regulatory framework. The recent portrayal of these companies as having ignored the requirements of the Constitution and failing to take appropriate environmental action has been populist rhetoric and mostly unfair to a number of award winning environmental projects and companies.

Certainly, companies would be prudent to protect their extensive capital investments by fully complying with reasonable and attainable international standards of environmental and health approvals for the well being of the environment and surrounding communities. Loading of NOX (Nitrous Oxide) and SOX (Sulfur Oxide) has been within standard in the Map Ta Phut area and, for several years, companies proposing new industrial projects have been trading emission capacity reductions at existing facilities through the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process.

There have been VOC (Volatile Organic Chemical) emission leaks, which is an area that, in the past, had not been measured. There were also some untimely process and logistics safety failures, both during construction and operations, which need to be scrutinized, with monitoring tightened and strictly enforced. There are a host of complex and detailed issues that explain how and why communities have been negatively impacted by industrial development and these issues need to be dramatically improved by industry and government alike, while also building increased trust, communications, planning and local community funding.

There is an initial approved list of eight types of industries that require EHIA approvals although there is disagreement and debate on whether this should be nineteen or an infinite number of projects if they contain even small amounts of chemicals. The independent committee that will render “opinions” to the approving government organization is still being formed. Thus, EHIA approvals will be slowly resolved and this further assumes the requirements and approvals are both reasonable and to international standards, and attainable by investors. So, the Map Ta Phut crisis will linger in 2010.

Investment Climate Setbacks

There have been numerous factors that have caused Thailand’s investment climate to deteriorate. Politics have been fractured and has left successive governments without a mandate to implement programs that will have long-term investment and infrastructure benefits as opposed to populist short term stimulus spending. In general, though, infrastructure in Thailand is a positive.

Energy policy remains chaotic, with subsidized cooking fuel being used for vehicles and requiring the importation of LPG at a time when refineries are operating below capacity, and natural gas for vehicles subsidized at unsustainable levels. All of which distorts the energy economics of the correct fuel choice for the consumer and the fuel model reliance for the producer as well. In addition, highway infrastructure budgets are under-funded as local roads and constituencies have received these diverted funds.

Other countries are moving ahead in telecom and liberalization of services, 3G services have not been implemented yet, as these sectors have been slow to open.

Policies making it more restrictive for labor practices and labor mobility as well as aggressive labor tactics have reduced Thailand’s attractiveness and directly deterred investment. Investor sentiment is further dampened by anti-foreign practices relating to home ownership, not approving permanent residency permits, and various proposed visa and work permit restrictions.

In various investment climate rankings, such as the World Economic Forum, Thailand’s ranking has deteriorated to # 36 in 2009 from # 28 in 2007. Supported by studies like the Doing Business 2010 by the Doing Business project at the World Bank Group, one would still conclude that overall investors find more positive attributes in investing in Thailand.

Restoring Industrial Growth and Competitiveness

Restoring industrial growth in manufacturing and demand for developed industrial land in industrial estates for either capital or technology-intensive manufacturing has started to come back. In a 2009 mid-year survey on Japanese Foreign Direct Investment, chemicals was the most promising industrial sector cited by JBIC (Japan Bank for International Cooperation) … a ranking that would certainly be lower in the wake of the Map Ta Phut situation. Automotive, given the survey timing in the heart of the global economic downturn, dropped to a much lower ranking.

However, as automotive volumes have returned and with Thailand’s ranking as the # 14 automotive producer in the world, opportunities for growth are returning and we have experienced heightened activity in this industry. Interesting has been the growth in exports of Original Equipment Manufacturers “OEMs” vehicle products and auto parts over the last ten years. Domestic auto demand has been stagnant since 1995 while 2010 sales are unlikely to reach much more than the 596,000 units sold 15 years ago.

Domestic market demand is the key to Thailand’s opportunity to produce a more robust automotive product line with innovative, not detuned local-only, products as a way to increase automotive production capabilities. Much of the recent expansion by Toyota has been mainstream passenger car models. The opening of the plant expansion by Ford and Mazda in 2009 was for “B” class small vehicles, the hot selling Mazda 2 and Ford Fiesta. Other production expansions by major automotive OEMs will have much the same theme, manufacturing mainstream, mostly passenger car, products.

Thailand would be better served by having the latest automotive products being affordable locally and to export automotive parts and OEM products where possible to the 10 million production volumes in Japan, the 4 million production volumes in Korea, the 1 million automotive demand in Australia, and potentially to China and to Thailand’s developed automotive export base of over 100 countries today.

The ECO car niche product being pursued by government policy will have limited success. Fuel prices in Thailand are relatively low, not prohibitive to drive purchases of very small cars unwanted by consumers. Much of the Thai population lives outside of urban areas where the 1-ton pickup will continue to be a better choice and, with low tax, diesel or subsidized fuel, not more expensive. Exports of the Thai ECO vehicle will find trade barriers to importation, thus restricting production, yet exports are required to qualify for investment incentives or to even make the volumes viable. Thai OEM’s will face competition from emerging countries, such as India, that have significantly higher ECO urban automotive volumes and more favorable supplier economies of scale.

Opportunities for 1-ton pickups, long the Thai vehicle champion and exported to130 countries seem to have leveled off. There are other SUV and crossover SUV products in which Thailand does not have a strong production base due to restricted local demand.

Countries that have strong sustainable automotive production and strong exports or potential export capabilities, e.g. U.S.A., Japan, Germany, Brazil, Mexico, Korea, China, and India, all have a common thread — a ready and competitive large local automotive market with, typically, a broad latest technological lineup of products. Thailand does not have this kind of domestic market due to high excise taxes and policies that discourage domestic consumption and, thus, will not fully develop this potential sustainable export market. This creates risks of lost future automotive investment to other growing local consumption markets, such as for ASEAN Indonesia and to a lesser extent Vietnam.

Industrial capacity in developed countries is now contracting and being rationalized. Thus, much of the industrial opportunity and expansion we see today is due to consolidation — including the selection of one country to use AFTA or various FTA’s to enhance export opportunities and trade, such as with Japan or Australia.

Other factors increasingly relevant after the crisis are to enhance competitiveness due to cost, currency, market access, and supplier base. Thailand has a well-developed and competitive automotive supplier base. The automotive industrial clusters such as the “Detroit of the East” automotive cluster with some 137 automotive suppliers and more than 220 auto factories at our Hemaraj Eastern Seaboard Industrial Estates offer a competitive advantage.

Both the private sector and government have roles in enhancing industrial productivity through increased capital investment and government incentives needed for this reinvestment. As well, streamlined standards, regulations, labor flexibility, and capacity building will increase competitiveness.

Forward thinking policies and a roadmap for energy, taxes, duties and excise are needed to enhance the local market consumption of automotive and other capital goods. Long term planning of economic and social development are required like our past experience with an active Eastern Seaboard Development Program. This would increase the predictability of policies so as not to have another Map Ta Phut setback as well as to provide the consistency and predictability needed for sustainable industrial development where communities and industry live in harmony. Manufacturing is an important sector for Thailand, representing some 35% of GDP. There are numerous environmental and industry success stories on which Thailand can build a long lasting competitive advantage with progressive policies for sustainable industrial development.